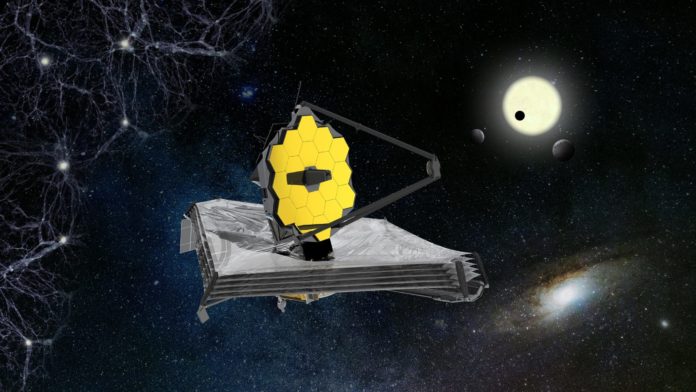

If all went as planned, by the time you read this, the James Webb Space Telescope will have deployed its tennis-court-sized sunshield and be well on its way to its final orbit point, one million miles from Earth, scheduled to be reached by month’s end.

The project, developed by NASA with contributions from the European and Canadian space agencies, was repeatedly delayed over some 30 years, during which time its cost ballooned to nearly $10 billion. But the expenditure has been justified by, if all goes well, the unprecedented view the telescope will provide of distant realms of the observable universe.

With its sunshield cooling its optics and instruments to –370° Fahrenheit, Webb will be able to register faint infrared light from a distance of more than 13 billion light years. (A single light year is about six trillion miles.) Scientists hope to glean knowledge from the new telescope that will explain how the first stars and galaxies formed since the universe’s creation in what is commonly called the Big Bang.

Until the 1960s, some pushed the “steady state” theory, positing that the universe had no beginning. Incontrovertible evidence emerged then, though, that there was indeed a Bereishis moment, as some of us knew all along.

Interestingly, astronauts on the Apollo 8 spacecraft—the first men to orbit the moon—took turns reading a translation of the first pesukim of Bereishis. (Fun fact: That recitation enraged a famous atheist of the time, Madalyn Murray O’Hair, who actually filed a lawsuit over, as she saw it, the unconstitutional injection of religion into a governmental program. The case was dismissed by the US Supreme Court “for want of jurisdiction.”)

The science community’s jubilation over Webb’s successful launching and potential revelations is understandable. But the celebration could do with a dash of humility.

If we pull back, as a telescope might do from a tree to show an entire forest, the limitations of even as ambitious and technologically amazing a feat as Webb come into view.

For starters, the Webb Telescope, unlike its relatively puny predecessor the Hubble, is sensitive primarily to the infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum. While it can peer deeper into space, it will lack the visual images the Hubble continues to provide.

Secondly, Webb’s life is limited. When it begins to run out of fuel in a few years, it won’t be able to maintain its orbit and point at its targets. Since it can’t be reached for repair by other spacecraft, when its fuel is gone, it will be mere spacejunk.

But most trenchant, though, is the fact that the size of the whole universe is unknown. No matter how far the infrared eyes of Webb might see, there will be much, perhaps infinitely much, beyond its purview. There is a reason the Lashon Hakodesh word for “universe,” olam, is a cognate of alem, “hidden.”

In 1987, Rav Mordechai Gifter, zt”l, wrote a letter to Rabbi Pinchas Stolper, in which the Telz rosh yeshivah quoted Albert Einstein. Einstein said that, despite the gargantuan advances in science in which he had played so pivotal a role, “our knowledge remains rather meager.” And, the celebrated physicist continued, “our increase in knowledge is comparable to that which a man, interested in learning more about the moon, gets when he climbs upon the roof of his house to catch a closer look at that luminary.”

The Webb Telescope will be immensely more revealing than a trip to the highest roof might provide, but, in the end, while it will add to human knowledge, it will not even scratch the surface of an ultimate understanding of the olam, and is sure to yield even more questions than the many open ones cosmologists already have.

But if it teaches the lesson that the more we learn about the universe, the more we know how little we know, the mission will have been a great success.